See more art at KathrynCarringtonFineArt.com

Carrington Sacred Art

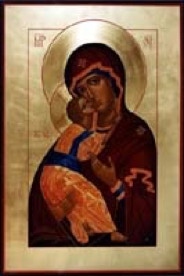

Gold leaf sacred icon paintings

of Jesus and Mary

by Kathryn Carrington

NEWS

Articles about Kathryn Carrington Sacred Art

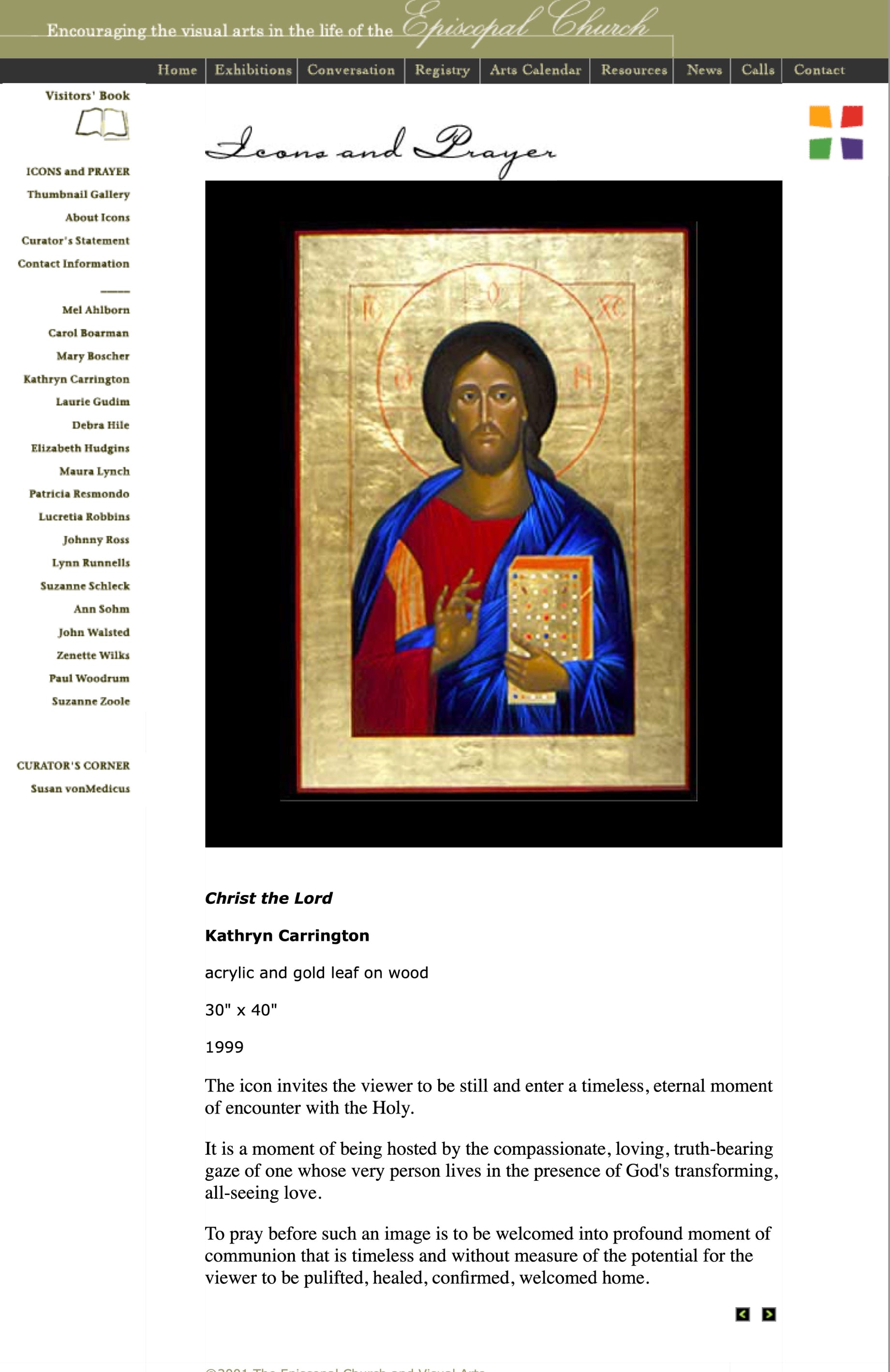

"The icon invites the viewer to be still and enter a timeless, eternal moment of encounter with the Holy.”

“It is a moment of being hosted by the compassionate, loving, truth-bearing gaze of one whose very person lives in the presence of God's transforming, all-seeing love.”

“To pray before such an image is to be welcomed into a profound moment of communion that is timeless and without measure of the potential for the viewer to be uplifted, healed, confirmed, welcomed home."

"A big part of icon painting is Tradition, with a capital T," she explained. That tradition has been treasured and protected for us by the Eastern church." She studied this tradition for years, working with a nun and a priest, and with masters of the technical aspects of Russian medieval church art. Her study, she said, combined beautifully with what she had learned earlier in the spiritual directors program of Shalem Institute for Spiritual Formation in Washington. She has painted many icons for churches, private collections and monasteries. Through her husband, Gregory, she met the presiding bishop, who had first visited Norbet's monastery as a priest in 1965. She came to know his wife, Phoebe, during the couple's years in Chicago. Carrington, who said Griswold carried with him one of her icons during the discernment process before his election as presiding bishop, said she was proud and pleased to have been asked to paint icons for the church center's chapel. She began the work in late 1998. "I pray for help as I paint the icon," she says. "I pray that the icon will inspire all those who will gaze upon it." Each icon slowly evolves, she said, revealing itself over months of time. "I wanted Christ to look very serene, and I wanted Mary to look tender, but strong." Both Christ and Mary are portrayed as dark-skinned people, not discernable as members of any specific race, she said, adding, "I strove to make Christ raceless. He transcends that." Griswold said he values the power and significance of icons. "They are a form of pictorial scripture that growing numbers of people in the West, who have been starved for something more intuitive to balance Western rationality, have found to be a window to divine mystery. "They are profoundly evocative. Because they come from the East, they transcend all the divisions we have experienced in Western Christianity. Maybe it's through icons that we are receiving a sense of mystery that has been so much a part of Eastern Christianity." Carrington says she can best describe the power of icons through the words of her friend, the Rev. Andrew Tregubov, author of "The Light of Christ," also published by St. Vladimir's Press: "Icons help us enter into communion with Christ and enlighten our souls. They become, in some mysterious way, the window to the divine and uncontainable God. Through the icon, the mystery of God is revealed in a direct way," he wrote. "The icon thus becomes a means of hope, a way of refuge and an experience of joy."

Kathryn McCormick, associate director of Episcopal News Service, contributed to this article. This article first appeared in the February 2000 "Episcopal Life" magazine. Republished by permission.

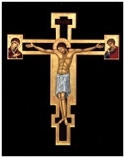

Icons, for many Christians of the Western world, are something of a mystery. Some see them as insignificant, flat, dark, primitive pieces of religious art and wonder at their popularity, while others regard them as a door into the divine realm and a means by which they can enter more deeply into their own interior life. "Icon" is a word generally used to describe religious pictures, mainly portable wood panel paintings, that have a historically prominent place in the life and worship of the Eastern Orthodox churches. From the Greek meaning "image," it is the word St. Paul used when he spoke of Jesus Christ being the image of the invisible God in the Epistle to the Colossians. Although icons grew out of the mosaic and fresco tradition of early Byzantine art, it was the Russian Orthodox Church that embraced iconography; it flourished there between the 15th and 19th centuries. Unlike Western art, which sought to reflect space and movement, icons focused on the symbolic or mystical aspects of the divine being.

Slowly, television, books, travel and a growing interest in Orthodox spirituality are contributing to a developing interest in icons and icon "writing." Scholars and restorers are opening the doors of perception, allowing Western Christians to better appreciate their beauty and power. "When noise and movement are increasingly dominant in our world -- and often our churches as well -- I believe it important that we should cherish those things that bring silence and stillness into our lives," says the Rev. John Baggley, writing about the spiritual significance of icons in "Doors of Perception" (St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, Crestwood, N.Y.). Baggley, an Anglican serving in the Church of England, says the lack of realism in icons has also been a major problem for Western people. Icon painters are not simply illustrators in the sense of pictures in religious books or Bibles, but their work is of a different category. "Just as the spoken or written word can convey the church's tradition and deepen the life of faith, so iconography is another means of conveying or externalizing the sacred tradition," Baggley says. "The purpose of an icon is to take us into the world of the Spirit, where we can experience the transforming power of divine grace." Because there are many variations in technique and a painter must master the skills of the art, knowing the materials and familiarity with the form and scale that is required for each subject, icon painting can be a daunting challenge to modern-day artists.

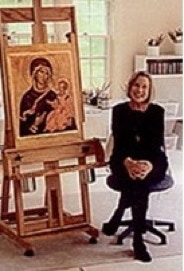

Therefore, it is surprising, even to her, that Kathryn Carrington, a successful artist, accepted that personal challenge. "The first time I saw an icon I thought it was awful," she recalls, laughing. This Vermont artist is enjoying life in her prime as a professional known widely for landscape watercolors and abstract paintings on handmade paper. They hang in hundreds of corporate and private collections. Since 1989, she has also been painting icons. Two of her most recent were dedicated in December in the Chapel of Christ the Lord at the Episcopal Church Center. Presiding Bishop Frank T. Griswold commissioned the works for the chapel along with two existing icons, one painted by the Rev. John Walsted of New York and another that was given to the late Presiding Bishop John Allin. "There are so many creative people in our church," Griswold said after the dedication. "I believe one of my functions is to bring attention and provide support to the talents of all those in our community.

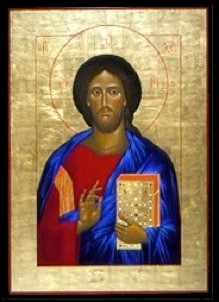

To artist Kathryn Carrington , icons are visual scripture, meant to complement the music and liturgy that regularly fill a church. The fact that two icons she has painted were recently installed in the Chapel of Christ the Lord at the Episcopal Church Center in New York City seems a natural step if the church is to consider all forms of art in worship. "I'm delighted, of course," she said in an interview on December 8, the day that the icons were dedicated in a service at which Presiding Bishop Frank T. Griswold presided. An Episcopalian, Carrington noted with a smile that of all the icons she has painted in her Manchester, Vermont, studio, these were the first to find homes in an Episcopal church. Griswold himself commissioned the works. After seeing them mounted on a wall, joining two other icons mounted elsewhere in the chapel, he declared he was "pleased beyond words. They are more beautiful than I had envisioned they might be." The dedication was a pleasing step in a remarkable journey that, Carrington admitted, "hasn't always been a piece of cake." The fact that she had painted them at all would at one time have seemed at odds with her life and work. "The first time I saw an icon I thought it was awful," she recalled, laughing. A graduate of the University of Michigan, where she earned bachelor's and master's degrees in fine arts, she also studied at Yale University, L'Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and Chelsea College in London. It was an impressive start, she agreed, but acknowledged later that her life also had taken her through some hard times. As a young widow with two children, she struggled as a single parent, then endured a long and debilitating illness that, for all its pain, nurtured her spiritual growth. She recovered, and eventually met Gregory Norbet , a former monk who has won distinction as a composer, speaker and retreat director. They married in 1987. "A friend sent us an icon card for our wedding," Carrington recalled. She said she set it on a mantle and found herself lighting candles near it and saying prayers. "After a year, I wondered if I could paint one. It just wouldn't go away." At that time she was busy as an artist (landscape watercolors and abstract paintings on her handmade paper) and an art consultant to many big firms and agencies. Her works are in the collections of IBM, Hyatt Regency, the U.S. State Department and Gannett Publishing, among others.

She made room in her life, however, to study the art of icons and their history. "A big part of icon painting is Tradition, with a capital T," she explained. That tradition, she added, "has been treasured and protected for us by the Eastern Church." Although icons grew out of the mosaic and fresco tradition of early Byzantine art, it was the Russian Orthodox Church that embraced iconography after Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Empire. Unlike western art, which sought to reflect space and movement, icon art focused on the symbolic or mystical aspects of the divine being. Carrington studied this tradition for years, working with a nun and a priest, and studying with masters of the technical aspects of medieval church art. The work combined beautifully with what she had learned earlier in the Spiritual Directors Program of Shalem Institute for Spiritual Formation in Washington, D.C. Her first icon was painted for a Roman Catholic parish on Long Island. She has painted others for churches, as well as private collections and for a monastery. She met Griswold through her husband; the presiding bishop first visited Norbet's monastery as a priest in 1965, she said. She added that she got to know Griswold's wife, Phoebe, during the years that Griswold served as bishop of Chicago. The bishop, in fact, commissioned a small icon from Carrington, which he carried with him while traveling during the discernment period before he was elected presiding bishop in 1997. When Griswold asked her to paint icons for the Church Center chapel, she said, she was proud and pleased to do them. Griswold noted that another icon in the chapel was the work of the Rev. John Walsted, an Episcopal priest from Staten Island, New York. A smaller icon was a gift to the late Presiding Bishop John Allin. "There are so many creative people in our church," Griswold said. "I believe one of my functions is to bring attention and provide support to the talents of all those in our community." Painting in prayer Carrington began painting her icons in late 1998. "I paint each icon in prayer," she said. "I believe that I am receiving help as I work on it, that Christ is in my work for people to see." Each icon slowly evolves, revealing itself over months of time, she said. Of the icons in the chapel, she said, "I wanted Christ to look very serene, and I wanted Mary to look tender, but strong." Both Christ and Mary are portrayed as dark-skinned people, not discernable as members of any specific race, she said, adding, "I strove to make Christ raceless. He transcends that." "Icons have their own power," Griswold said later. "They are a form of pictorial scripture. Growing numbers of people in the West, who have been starved for something more intuitive to balance western rationality, have found them to be a window to divine mystery. "They are profoundly interesting. Because they come from the East, they transcend all the divisions we have experienced in western Christianity. Maybe it's through icons that we are receiving a sense of mystery that has been so much a part of eastern Christianity."